Posts Tagged ‘National Trust’

The Folly of Touching The Void

January 19th, 2012by Gwyn Headley

Managing Director

Jacqui Norman, who never makes a mistake (or so she tells me) sent out a Picture Call this morning for some exciting mountaineering shots for the front cover of a Japanese novel titled “Hidako”.

Of course my knowledge of Japanese peaks is second to none, and the Hidaka range is well known to me (and Mr. Wikipedia). The highest peak is Mount Poroshiri at 6,785 feet. It’s not HidakO, it’s HidakA. But Jacqui says that if that’s what the client ordered, that’s what the client wants.

She said he wanted images to capture the thrills, excitement and danger of mountaineering anywhere, not just on some overblown Japanese hill. Like Joe Simpson’s “Into The Void”.

Ah. Wrong again, Jacqui. Joe Simpson’s “Touching The Void”, not “Into The Void” is one of the classics of mountaineering, as fotoLibra “8,000 Uploads!” member Nick Jenkins quickly pointed out.

And as I remember only too well, even without the aid of Mr. Wikipedia. I have never read the book, because I am consumed with jealousy.

Let me take you back to 1985. I had just delivered the manuscript of Wim Meulenkamp’s and my first book on follies to the gilded offices of Jonathan Cape in London’s Bedford Square (even the electric sockets were golden, there’s posh, yes?). Unfortunately my editor Liz Calder, who had commissioned the book, had left to co-found a new publisher called Bloomsbury, so our book was passed down to another editor, Tony Colwell.

Tony could spare me half an hour to talk about publicity. I was ushered into his office. He greeted me abstractedly. “This is a really wonderful book,” he muttered, shaking his head. “Oh!” I stammered. “Thank you so much!”

“No, no, I’m sorry, I was thinking about this mountaineering book,” he said. “It’s called “Touching The Void”, and it’s by this amazing man called Joe Simpson.”

And for the next 25 minutes Tony praised this incredible book, lauding it with superlative after superlative. He went on and on. I just sat there.

Eventually he glanced at his watch. “Goodness, is that the time? I suppose we’d better talk about your book. Well, we’ll be sending out the usual review copies. Is there anything else? Well, goodbye, so good of you to come in.”

And that was that.

Ever since then, any mention of Joe Simpson’s “Touching The Void” sets my teeth on edge.

I shouldn’t really complain, because Jonathan Cape ended up doing a really spectacular publicity job on “Follies”, and it sold out in 11 months.

And if you want to see a REALLY plush publisher’s office, you should visit Bloomsbury, the company that Liz Calder co-founded. Spread over three town houses in the same Bedford Square, they might as well have gilded the entire interior, such is its opulence. I guess Harry Potter contributed a penny or two.

Oh — and congratulations are due to Nick Jenkins. 8,000 images is one impressive portfolio! Other members could learn a lot from him — and they can, because Nick runs some great photography courses at Freespirit Images.

Orphan Books

December 23rd, 2009by Gwyn Headley

Managing Director

The New York Times has published its annual list of ‘buzzwords of the year’. Two have been derived from book publishing, in which fotoLibra has a vested interest as publishers constitute our largest single market.

The words are ‘Vook’ and ‘Orphan Books’. ‘Vook’ is a neologism and ‘Orphan Books’ is a phrase rather than a word, but we’ll let that pass. Let’s deal with Vook first: its etymology is a combination of Video and bOOK content, in other words the killer ebook I described in this blog post without using the word vook. More recently, I got rather excited by this ad for Sports Illustrated which pretty accurately delivered what I was looking for in an ebook, only as a magazine. So what would this be? A vazine? Videodical? A Vag (Video mAGazine)?

Anyway, the first time I ever heard the term ‘vook’ was when I read the article this morning. So I’m not aware of it as a buzz word.

Orphan Books are defined by the New York Times as “volumes still in copyright but out of print and unavailable for sale, and whose copyright holders cannot be found.” The article says that the term ‘Orphan Book’ first rose to prominence in 2007, but “peaked this year with the fierce discussion over the proposed Google Books settlement.”

Orphan Book has a completely different meaning for me and many other authors and publishers. The real Orphan Book is one that is orphaned at birth, a tragedy shared with genuine orphans.

When an editor commissions a book and leaves the firm before the book is published, that creates an orphan book. Within a publishing house, the editor’s rôle is to deliver the best product he can, and to do that he has to talk up his babies to publicity, sales, marketing and of course the board. His books are better than the books from the other editors in the house; they are more marketable, better written, more intelligent, bigger sellers, indeed seminal. Few can remain unimpressed at the sight of an editor firing on all 16 cylinders to promote a favoured author or title at a sales conference.

But if that editor is no longer there to defend and promote the title, what happens to the book? I can tell you from bitter experience — it’s forgotten. There’s a contract, so the company is obliged to issue the book, but because no one remaining in the company is interested, it is not so much published as released into the community.

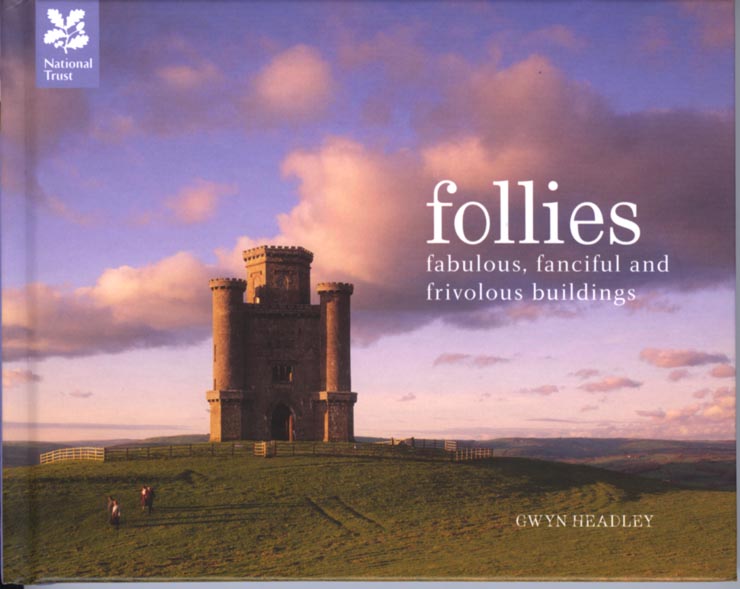

Three of my books were orphan books: Follies: A National Trust Guide: commissioned by Robin Wright (died shortly afterwards) and Liz Calder (left to found Bloomsbury). Eventually published by Jonathan Cape, 1986.

Architectural Follies In America: commissioned by Buckley Jeppson of the Preservation Press. Buckley left, the company was acquired by John Wiley & Son and the book was eventually published by them in 1996.

The Encyclopaedia of Fonts: Commissioned by Jane Ellis. Jane left over a year before a new managing director eventually allowed the book to trickle out in mid-December. Eventually published by Cassell Illustrated, 2005.

So where does the New York Times get Orphan Books from, to mean this quasi-legal grey area? From Google, of course. Google is not a book publisher and does not use a book publishing vocabulary, so it created this term to describe what is in fact a minute sector of the market. How many titles are we talking about in Google’s definition of an ‘orphan book’? How many books are there where the copyright holders cannot be found? Who is looking for them? How hard are they looking?

If I owe somebody money, they always manage to find me. But if money is owed to me, the difficulty of tracking me down becomes exponentially greater. Creating a snappy phrase — even by appropriating one that’s already in use within the trade for a common occurrence — gives visibility to an otherwise overlooked and unimportant sector of the market.

And interestingly it might help to divert attention from much larger, yet less transparent, activities being carried on elsewhere.